As a data scientist, I don’t often encounter design patterns. However, I found the Builder Design Pattern particularly challenging when I came across it in Chapter 03 of the LLM Engineer’s Handbook.

In this fast-paced world—and as a human among AI agents 😜—I want to take a moment to share what I’ve learned, hoping to assist fellow data scientists (and anyone else!) who might face a similar challenge.

In this post, I’ll explain the Builder Design Pattern as it is implemented in the book.

Don’t worry—reading the book isn’t necessary to follow along.

What are we trying to build?

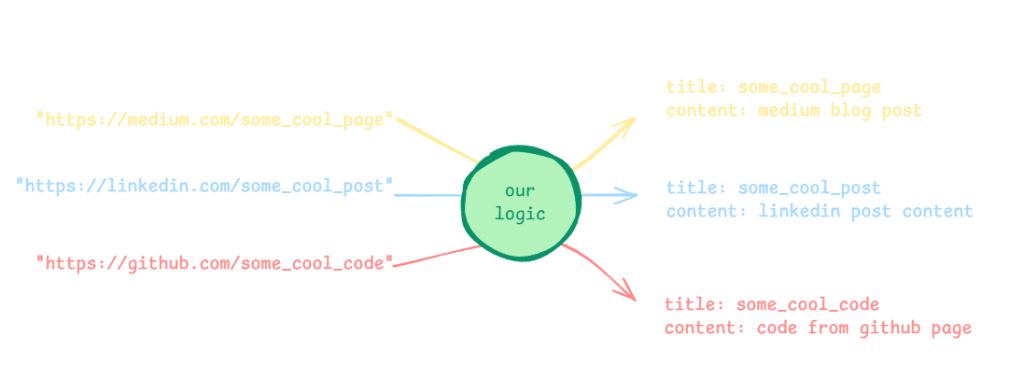

We want to build some logic (i.e. a function) that takes a list of website links (e.g., Medium, LinkedIn posts, and GitHub) as input and outputs the content of these links. We want this logic to be flexible enough to add any new websites in the future without affecting the logic structure.

The challenge

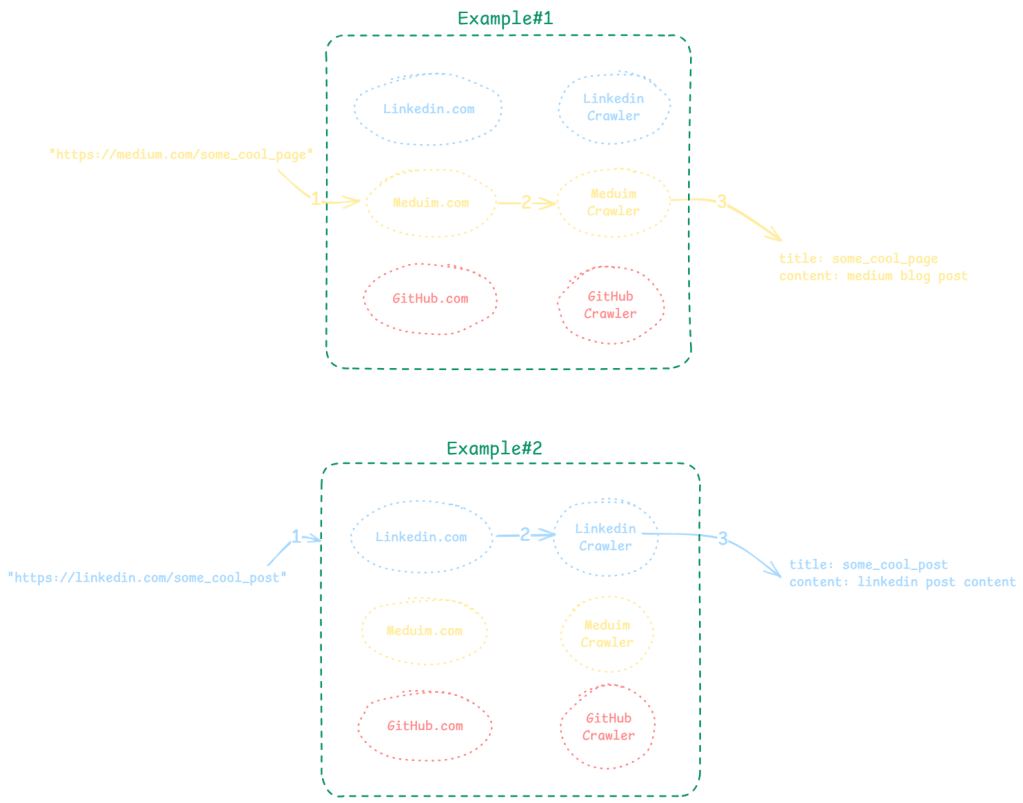

Since the website links do not belong to a single website and originate from different websites, the crawling mechanics will vary from one site to another. This could complicate our logic, as we aim to automate the process in three steps (as shown in the illustration below):

- Recognize the website.

- Determine the correct crawling mechanism for that website.

- Apply the appropriate mechanism to crawl it.

The solution:

Now, there are two ways to handle this:

Option 1: Use Multiple if Statements

This would be my first (and maybe naive) approach. For every link, the function checks the domain of the website link, and then it uses the correct crawler accordingly.

link = "https://medium.com/cool_stuff"

domain = extract_domain_from_link(link)

if domain == "medium.com":

content = medium_crawler(link)

if domain == "linkedin.com":

content = linkedin_crawler(link)

if domain == "github.com":

content = github_crawler(link)

This approach becomes messy and hard to maintain as the list of websites grows.

For example: every new site introduces a potential for bugs in my already tangled logic.

Option 2: Use a Builder Design Pattern

The book approaches this challenge differently by utilizing the Builder Design Pattern. This design pattern constructs complex objects step by step, rather than in a single complex step, providing both flexibility and clarity to the code.

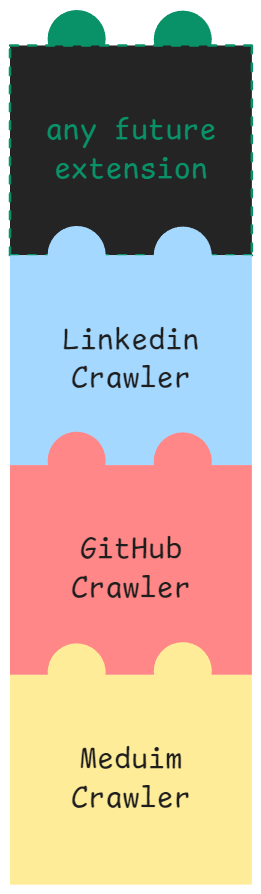

For instance, if we want to create a crawler with multiple capabilities—such as crawling Medium, LinkedIn, and GitHub—these capabilities can be added incrementally, much like assembling Lego bricks. Using this pattern makes it easy to add additional features and ensures that the system remains flexible and expandable.

The code (full code on GitHub) implements it by creating a class called CrawlerDispatcher, which helps select the correct type of crawler to handle a given URL link.

This class has two distinct behaviors as we will explore their benefits later:

1- it instantiate the objects outside of the __init__ block.

2- every step added (i.e., via methods) returns self, which I think is unique to this design pattern.

The __init__ block:

Here is the __init__ block in the CrawlerDispatcher class. It just initiates an empty dictionary self._crawlers.

class CrawlerDispatcher:

def __init__(self) -> None:

self._crawlers = {}

# ... (rest of the class is not important for now)...

Think of this dictionary as a phone book or even a switchboard operator: depending on the link you provide, it chooses the appropriate tool (crawler) that is available (i.e., registered) to process that URL.

The rest of the class has the following main parts (which will be explained in detail in the sections below)

- The

buildmethod (pink block below): responsible forbuildingthe differentcrawlersobjects. Here, objects are instantiated instead of the__init__block. - The

registermethods (blue block below): these are the steps …The added or registeredcrawlersfor different sites - The

get_registermethod (green block below): choose the bestcrawlersobject for each URL link

class CrawlerDispatcher:

def __init__(self) -> None:

self._crawlers = {}

@classmethod

def build(cls) -> "CrawlerDispatcher":

# ... (some logic)...

def register(self, domain, crawler):

# ... (some logic)...

def register_medium(self) -> "CrawlerDispatcher":

# ... (some logic)...

def register_linkedin(self) -> "CrawlerDispatcher":

# ... (some logic)...

def register_github(self) -> "CrawlerDispatcher":

# ... (some logic)...

def get_crawler(self, url: str) -> BaseCrawler:

# ... (some logic)...

Let’s explore these blocks one by one in the next section.

The build method:

@classmethod

def build(cls) -> "CrawlerDispatcher":

dispatcher = cls()

return dispatcher

The build method is a special kind of method. It’s called a “class method” (hence the @classmethod decorator above the function), and its main job is to create and return an instance of the CrawlerDispatcher class. It is kind of similar to creating the instance manually like the code below (but better, for the reasons I’ll explain below).

new_dispatcher_object = CrawlerDispatcher()

Why the build() method is better than the code above?

It provides more flexibility. For example, when we create a new object using CrawlerDispatcher(), the __init__ method is automatically called. However, this approach is rigid because it ties object creation directly to the __init__ method’s implementation.

The build method acts as a separate, customizable layer over the constructor (i.e. initializer). It allows you to define how objects are created without modifying or overloading __init__.

It also allows for customized object creation and enables future extensibility without tightly coupling the initialization logic to the constructor (__init__).

Moreover, it makes your code easier to read. For example, calling CrawlerDispatcher.build() makes it obvious that the class instance is being created in a deliberate way with some additional logic, instead of just relying on the default constructor behavior.

This separation ensures that the constructor remains clean and focused on initializing the object’s core attributes, while build handles anything extra.

If you call

CrawlerDispatcher.build(), it’s like saying: “Hey, give me a newCrawlerDispatcherinstance!” … as simple as that 🙂

The register Methods

You can think of this part as a fancy way to create a dictionary that associates a website domain pattern (e.g., https://medium.com and https://www.medium.com) as keys, with a specific crawler class (e.g., MediumCrawler) as values. So the final result would look like this:

import MediumCrawler, LinkedInCrawler, GithubCrawler

the_final_result= {r"https://(www\.)?medium\.com/*", MediumCrawler,r"https://(www\.)?linkedin\.com/*", LinkedInCrawler,r"https://(www\.)?github\.com/*", GithubCrawler}

This is very similar to the green boxes in Figure02 above.

These crawler classes (MediumCrawler, LinkedInCrawler, GithubCrawler) are imported from a different part of the code, and the content of these classes is not important for now. However, the important bit is that all these crawlers have the same signature, yet each class handles a specific website.

Let’s have a look at the register method. It takes the domain and the crawler as inputs

def register(self, domain, crawler) -> None:

parsed_domain = urlparse(domain)

domain = parsed_domain.netloc

self._crawlers[r"https://(www\.)?{}/*"

.format(re.escape(domain))] = crawler

and does the following:

- Extract Domain:

- The domain is parsed using

urlparse(domain)to ensure it is clean. parsed_domain.netlocis used to extract the hostname (e.g.,medium.com).

- The domain is parsed using

- Generate Regex Pattern:

- A regex pattern is created to match URLs from the domain. For instance:

r"https://(www\.)?medium\.com/*"This ensures the pattern matches bothhttps://medium.comandhttps://www.medium.com.

- A regex pattern is created to match URLs from the domain. For instance:

- Register the Pattern:

- The pattern is added as a key to the

_crawlersdictionary, with the corresponding crawler class as its value.

- The pattern is added as a key to the

and the final result is something like this:

self._crawlers= {r"https://(www\.)?medium\.com/*", MediumCrawler,r"https://(www\.)?linkedin\.com/*", LinkedInCrawler,r"https://(www\.)?github\.com/*", GithubCrawler}

then, we implement the register method 3 times for the three websites:

def register_medium(self) -> "CrawlerDispatcher":

self.register("https://medium.com", MediumCrawler)

return self

def register_linkedin(self) -> "CrawlerDispatcher":

self.register("https://linkedin.com", LinkedInCrawler)

return self

def register_github(self) -> "CrawlerDispatcher":

self.register("https://github.com", GithubCrawler)

return self

Notice here that each of these methods returns self, which basically returns the object after adding/registering the crawlers… Each one of these methods is a step to build our complex crawler … one step means one new capability.

returning self gives this pattern one of its unique characters… chaining… it means you can add a chain of steps, one after another (see the code below), which indeed resembles Lego bricks. We will visit this code in the next section, but in short, it means adding the ability to crawl Medium, and then adding the ability to crawl LinkedIn, and adding the ability to crawl GitHub… isn’t that beautiful?

dispatcher.register_medium().register_linkedin().register_github()

This design is flexible and allows the addition of new crawlers without modifying existing logic. For example: dispatcher.register_medium() means: “Make the dispatcher know how to handle Medium URLs.”

The get_crawler Method

This method’s purpose is to find and return the appropriate crawler for a given URL.

def get_crawler(self, url: str) -> BaseCrawler:

for pattern, crawler in self._crawlers.items():

if re.match(pattern, url):

return crawler()

else:

return CustomArticleCrawler()

It does the following:

- Match URL with Patterns:

- Iterate through the

_crawlersdictionary. - Use

re.match(pattern, url)to check if the URL matches any of the registered patterns.

- Iterate through the

- Return Matched Crawler:

- If a match is found, return an instance of the associated crawler class.

- Fallback to Default:

- If no pattern matches, log a warning and return an instance of

CustomArticleCrawler.

- If no pattern matches, log a warning and return an instance of

How can we use this class?

Step 1: Build a Dispatcher

dispatcher = CrawlerDispatcher.build()This creates an empty dispatcher.

Step 2: Register Some Crawlers

dispatcher.register_medium().register_linkedin().register_github()

Now the dispatcher knows how to handle Medium, LinkedIn, and GitHub URLs.

Step 3: Use the Dispatcher to Get a Crawler

crawler = dispatcher.get_crawler("https://medium.com/some-article")

- The dispatcher sees the URL matches the Medium pattern.

- It returns an instance of

MediumCrawler.

That’s it. If you think this post was useful, please share it to others so they can enjoy this amazing book!